Nonlinear optics

Nonlinear optics (NLO) is the branch of optics that describes the behavior of light in nonlinear media, that is, media in which the dielectric polarization P responds nonlinearly to the electric field E of the light. This nonlinearity is typically only observed at very high light intensities (values of the electric field comparable to interatomic electric fields, typically 108 V/m) such as those provided by pulsed lasers. In nonlinear optics, the superposition principle no longer holds.

Nonlinear optics remained unexplored until the discovery of Second harmonic generation shortly after demonstration of the first laser. (Peter Franken et al at University of Michigan in 1961)

Contents |

Nonlinear optical processes

Nonlinear optics gives rise to a host of optical phenomena:

Frequency mixing processes

- Second harmonic generation (SHG), or frequency doubling, generation of light with a doubled frequency (half the wavelength), two photons are destroyed creating a single photon at two times the frequency.

- Third harmonic generation (THG), generation of light with a tripled frequency (one-third the wavelength), three photons are destroyed creating a single photon at three times the frequency.

- High harmonic generation (HHG), generation of light with frequencies much greater than the original (typically 100 to 1000 times greater)

- Sum frequency generation (SFG), generation of light with a frequency that is the sum of two other frequencies (SHG is a special case of this)

- Difference frequency generation (DFG), generation of light with a frequency that is the difference between two other frequencies

- Optical parametric amplification (OPA), amplification of a signal input in the presence of a higher-frequency pump wave, at the same time generating an idler wave (can be considered as DFG)

- Optical parametric oscillation (OPO), generation of a signal and idler wave using a parametric amplifier in a resonator (with no signal input)

- Optical parametric generation (OPG), like parametric oscillation but without a resonator, using a very high gain instead

- Spontaneous parametric down conversion (SPDC), the amplification of the vacuum fluctuations in the low gain regime

- Optical rectification (OR), generation of quasi-static electric fields.

- Nonlinear light-matter interaction with free electrons and plasmas[1][2][3][4]

Other nonlinear processes

- Optical Kerr effect, intensity dependent refractive index (a

effect)

effect)

- Self-focusing, an effect due to the Optical Kerr effect (and possibly higher order nonlinearities) caused by the spatial variation in the intensity creating a spatial variation in the refractive index

- Kerr-lens modelocking (KLM), the use of Self-focusing as a mechanism to mode lock laser.

- Self-phase modulation (SPM), an effect due to the Optical Kerr effect (and possibly higher order nonlinearities) caused by the temporal variation in the intensity creating a temporal variation in the refractive index

- Optical solitons, An equilibrium solution for either an optical pulse (temporal soliton) or Spatial mode (spatial soliton) that does not change during propagation due to a balance between diffraction and the Kerr effect (e.g. Self-phase modulation for temporal and Self-focusing for spatial solitons).

- Cross-phase modulation (XPM)

- Four-wave mixing (FWM), can also arise from other nonlinearities

- Cross-polarized wave generation (XPW), a

effect in which a wave with polarization vector perpendicular to the input one is generated

effect in which a wave with polarization vector perpendicular to the input one is generated - Modulational instability

- Raman amplification

- Optical phase conjugation

- Stimulated Brillouin scattering, interaction of photons with acoustic phonons

- Multi-photon absorption, simultaneous absorption of two or more photons, transferring the energy to a single electron

- Multiple photoionisation, near-simultaneous removal of many bound electrons by one photon

- Chaos in Optical Systems

Related processes

In these processes, the medium has a linear response to the light, but the properties of the medium are affected by other causes:

- Pockels effect, the refractive index is affected by a static electric field; used in electro-optic modulators;

- Acousto-optics, the refractive index is affected by acoustic waves (ultrasound); used in acousto-optic modulators.

- Raman scattering, interaction of photons with optical phonons;

Parametric processes

Nonlinear effects fall into two qualitatively different categories, parametric and non-parametric effects. A parametric non-linearity is an interaction in which the quantum state of the nonlinear material is not changed by the interaction with the optical field. As a consequence of this, the process is 'instantaneous'; Energy and momentum conserving in the optical field, making phase matching important; and polarization dependent. [5] [6]

Theory

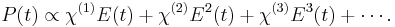

Parametric and lossy 'instantaneous' (i.e. electronic) nonlinear optical phenomena, in which the optical fields are not too large, can be described by a Taylor series expansion of the dielectric Polarization density (dipole moment per unit volume) P(t) at time t in terms of the electrical field:

Here, the coefficients χ(n) are the n-th order susceptibilities of the medium and the presence of such a term is generally referred to as an n-th order nonlinearity. In general χn is an n+1 order tensor representing both the polarization dependent nature of the parametric interaction as well as the symmetries (or lack thereof) of the nonlinear material.

Wave-equation in a nonlinear material

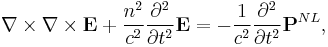

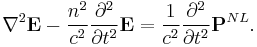

Central to the study of electromagnetic waves is the wave equation. Starting with Maxwell's equations in an isotropic space containing no free charge, it can be shown that:

where PNL is the nonlinear part of the Polarization density and n is the refractive index which comes from the linear term in P.

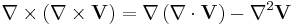

Note one can normally use the vector identity

and Gauss's law,

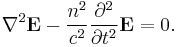

to obtain the more familiar wave equation

For nonlinear medium Gauss's law does not imply that the identity

is true in general, even for an isotropic medium. However even when this term is not identically 0, it is often negligibly small and thus in practice is usually ignored giving us the standard nonlinear wave-equation:

Nonlinearities as a wave mixing process

The nonlinear wave-equation is an inhomogeneous differential equation. The general solution comes from the study of Ordinary differential equations and can be solved by the use of a Green's function. Physically one gets the normal electromagnetic wave solutions to the homogeneous part of the wave equation:

and the inhomogenous term

acts as a driver/source of the electromagnetic waves. One of the consequences of this is a nonlinear interaction will result in energy being mixed or coupled between different colors which is often called a 'wave mixing'.

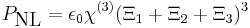

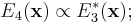

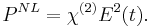

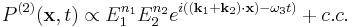

In general an n-th order will lead to n+1-th wave mixing. As an example, if we consider only a second order nonlinearity (three-wave mixing), then the polarization, P, takes the form

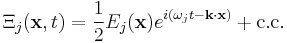

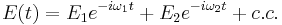

If we assume that E(t) is made up of two colors at frequencies ω1 and ω2, we can write E(t) as

where c.c. stands for complex conjugate. Plugging this into the expression for P gives

which has frequency components at 2ω1,2ω2, ω1+ω2, ω1-ω2, and 0. These three-wave mixing processes correspond to the nonlinear effects known as Second harmonic generation, Sum frequency generation, Difference frequency generation and Optical rectification respectively.

Note: Parametric generation and amplification is a variation of difference frequency generation, where the lower-frequency of one of the two generating fields is much weaker (parametric amplification) or completely absent (parametric generation). In the latter case, the fundamental quantum-mechanical uncertainty in the electric field initiates the process.

Phase matching

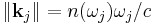

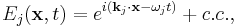

The above ignores the position dependence of the electrical fields. In a typical situation, the electrical fields are traveling waves described by

at position  , with the wave vector

, with the wave vector  , where

, where  is the velocity of light and

is the velocity of light and  the index of refraction of the medium at angular frequency

the index of refraction of the medium at angular frequency  . Thus, the second-order polarization at angular frequency

. Thus, the second-order polarization at angular frequency  is

is

At each position  within the nonlinear medium, the oscillating second-order polarization radiates at angular frequency

within the nonlinear medium, the oscillating second-order polarization radiates at angular frequency  and a corresponding wave vector

and a corresponding wave vector  . Constructive interference, and therefore a high intensity

. Constructive interference, and therefore a high intensity  field, will occur only if

field, will occur only if

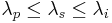

The above equation is known as the phase matching condition. Typically, three-wave mixing is done in a birefringent crystalline material (I.e., the refractive index depends on the polarization and direction of the light that passes through.), where the polarizations of the fields and the orientation of the crystal are chosen such that the phase-matching condition is fulfilled. This phase matching technique is called angle tuning. Typically a crystal has three axes, one or two of which have a different refractive index than the other one(s). Uniaxial crystals, for example, have a single preferred axis, called the extraordinary (e) axis, while the other two are ordinary axes (o) (see crystal optics). There are several schemes of choosing the polarizations for this crystal type. If the signal and idler have the same polarization, it is called "Type-I phase-matching", and if their polarizations are perpendicular, it is called "Type-II phase-matching". However, other conventions exist that specify further which frequency has what polarization relative to the crystal axis. These types are listed below, with the convention that the signal wavelength is shorter than the idler wavelength.

| Polarizations | Scheme | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Pump | Signal | Idler | |

| e | o | o | Type I |

| e | o | e | Type II (or IIA) |

| e | e | o | Type III (or IIB) |

| e | e | e | Type IV |

| o | o | o | Type V |

| o | o | e | Type VI (or IIB or IIIA) |

| o | e | o | Type VII (or IIA or IIIB) |

| o | e | e | Type VIII (or I) |

Most common nonlinear crystals are negative uniaxial, which means that the e axis has a smaller refractive index than the o axes. In those crystals, type I and II phasematching are usually the most suitable schemes. In positive uniaxial crystals, types VII and VIII are more suitable. Types II and III are essentially equivalent, except that the names of signal and idler are swapped when the signal has a longer wavelength than the idler. For this reason, they are sometimes called IIA and IIB. The type numbers V–VIII are less common than I and II and variants.

One undesirable effect of angle tuning is that the optical frequencies involved do not propagate collinearly with each other. This is due to the fact that the extraordinary wave propagating through a birefringent crystal possesses a Poynting vector that is not parallel with the propagation vector. This would lead to beam walkoff which limits the nonlinear optical conversion efficiency. Two other methods of phase matching avoids beam walkoff by forcing all frequencies to propagate at a 90 degree angle with respect to the optical axis of the crystal. These methods are called temperature tuning and quasi-phase-matching.

Temperature tuning is where the pump (laser) frequency polarization is orthogonal to the signal and idler frequency polarization. The birefringence in some crystals, in particular Lithium Niobate is highly temperature dependent. The crystal is controlled at a certain temperature to achieve phase matching conditions.

The other method is quasi-phase matching. In this method the frequencies involved are not constantly locked in phase with each other, instead the crystal axis is flipped at a regular interval Λ, typically 15 micrometres in length. Hence, these crystals are called periodically poled. This results in the polarization response of the crystal to be shifted back in phase with the pump beam by reversing the nonlinear susceptibility. This allows net positive energy flow from the pump into the signal and idler frequencies. In this case, the crystal itself provides the additional wavevector k=2π/λ (and hence momentum) to satisfy the phase matching condition. Quasi-phase matching can be expanded to chirped gratings to get more bandwidth and to shape an SHG pulse like it is done in a dazzler. SHG of a pump and Self-phase modulation (emulated by second order processes) of the signal and an optical parametric amplifier can be integrated monolithically.

Higher-order frequency mixing

The above holds for  processes. It can be extended for processes where

processes. It can be extended for processes where  is nonzero, something that is generally true in any medium without any symmetry restrictions. Third-harmonic generation is a

is nonzero, something that is generally true in any medium without any symmetry restrictions. Third-harmonic generation is a  process, although in laser applications, it is usually implemented as a two-stage process: first the fundamental laser frequency is doubled and then the doubled and the fundamental frequencies are added in a sum-frequency process. The Kerr effect can be described as a

process, although in laser applications, it is usually implemented as a two-stage process: first the fundamental laser frequency is doubled and then the doubled and the fundamental frequencies are added in a sum-frequency process. The Kerr effect can be described as a  as well.

as well.

At high intensities the Taylor series, which led the domination of the lower orders, does not converge anymore and instead a time based model is used. When a noble gas atom is hit by an intense laser pulse, which has an electric field strength comparable to the Coulomb field of the atom, the outermost electron may be ionized from the atom. Once freed, the electron can be accelerated by the electric field of the light, first moving away from the ion, then back toward it as the field changes direction. The electron may then recombine with the ion, releasing its energy in the form of a photon. The light is emitted at every peak of the laser light field which is intense enough, producing a series of attosecond light flashes. The photon energies generated by this process can extend past the 800th harmonic order up to 1300 eV. This is called high-order harmonic generation. The laser must be linearly polarized, so that the electron returns to the vicinity of the parent ion. High-order harmonic generation has been observed in noble gas jets, cells, and gas-filled capillary waveguides.

Example uses of nonlinear optics

Frequency doubling

One of the most commonly used frequency-mixing processes is frequency doubling or second-harmonic generation. With this technique, the 1064-nm output from Nd:YAG lasers or the 800-nm output from Ti:sapphire lasers can be converted to visible light, with wavelengths of 532 nm (green) or 400 nm (violet), respectively.

Practically, frequency-doubling is carried out by placing a nonlinear medium in a laser beam. While there are many types of nonlinear media, the most common media are crystals. Commonly used crystals are BBO (β-barium borate), KDP (potassium dihydrogen phosphate), KTP (potassium titanyl phosphate), and lithium niobate. These crystals have the necessary properties of being strongly birefringent (necessary to obtain phase matching, see below), having a specific crystal symmetry and of course being transparent for both the impinging laser light and the frequency doubled wavelength, and have high damage thresholds which make them resistant against the high-intensity laser light. However, organic polymeric materials are set to take over from crystals as they are cheaper to make, have lower drive voltages and superior performance.

Optical phase conjugation

It is possible, using nonlinear optical processes, to exactly reverse the propagation direction and phase variation of a beam of light. The reversed beam is called a conjugate beam, and thus the technique is known as optical phase conjugation[8][9] (also called time reversal, wavefront reversal and retroreflection).

One can interpret this nonlinear optical interaction as being analogous to a real-time holographic process.[10] In this case, the interacting beams simultaneously interact in a nonlinear optical material to form a dynamic hologram (two of the three input beams), or real-time diffraction pattern, in the material. The third incident beam diffracts off this dynamic hologram, and, in the process, reads out the phase-conjugate wave. In effect, all three incident beams interact (essentially) simultaneously to form several real-time holograms, resulting in a set of diffracted output waves that phase up as the "time-reversed" beam. In the language of nonlinear optics, the interacting beams result in a nonlinear polarization within the material, which coherently radiates to form the phase-conjugate wave.

The most common way of producing optical phase conjugation is to use a four-wave mixing technique, though it is also possible to use processes such as stimulated Brillouin scattering. A device producing the phase conjugation effect is known as a phase conjugate mirror (PCM).

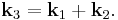

For the four-wave mixing technique, we can describe four beams (j = 1,2,3,4) with electric fields:

where Ej are the electric field amplitudes. Ξ1 and Ξ2 are known as the two pump waves, with Ξ3 being the signal wave, and Ξ4 being the generated conjugate wave.

If the pump waves and the signal wave are superimposed in a medium with a non-zero χ(3), this produces a nonlinear polarization field:

resulting in generation of waves with frequencies given by ω = ±ω1 ±ω2 ±ω3 in addition to third harmonic generation waves with ω = 3ω1, 3ω2, 3ω3.

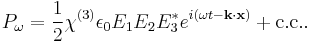

As above, the phase-matching condition determines which of these waves is the dominant. By choosing conditions such that ω = ω1 + ω2 - ω3 and k = k1 + k2 - k3, this gives a polarization field:

This is the generating field for the phase conjugate beam, Ξ4. Its direction is given by k4 = k1 + k2 - k3, and so if the two pump beams are counterpropagating (k1 = -k2), then the conjugate and signal beams propagate in opposite directions (k4 = -k3). This results in the retroreflecting property of the effect.

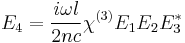

Further, it can be shown for a medium with refractive index n and a beam interaction length l, the electric field amplitude of the conjugate beam is approximated by

(where c is the speed of light). If the pump beams E1 and E2 are plane (counterpropagating) waves, then:

that is, the generated beam amplitude is the complex conjugate of the signal beam amplitude. Since the imaginary part of the amplitude contains the phase of the beam, this results in the reversal of phase property of the effect.

Note that the constant of proportionality between the signal and conjugate beams can be greater than 1. This is effectively a mirror with a reflection coefficient greater than 100%, producing an amplified reflection. The power for this comes from the two pump beams, which are depleted by the process.

The frequency of the conjugate wave can be different from that of the signal wave. If the pump waves are of frequency ω1 = ω2 = ω, and the signal wave higher in frequency such that ω3 = ω + Δω, then the conjugate wave is of frequency ω4 = ω - Δω. This is known as frequency flipping.

Common SHG materials

- 800 nm light : BBO

- 806 nm light : lithium iodate (LiIO3)

- 860 nm light : potassium niobate (KNbO3)

- 980 nm light : KNbO3

- 1064 nm light : monopotassium phosphate (KH2PO4, KDP), lithium triborate (LBO) and β-barium borate (BBO).

- 1300 nm light : gallium selenide (GaSe)

- 1319 nm light : KNbO3, BBO, KDP, potassium titanyl phosphate (KTP), lithium niobate (LiNbO3), LiIO3, and ammonium dihydrogen phosphate (ADP)

- 1550 nm light : potassium titanyl phosphate (KTP), lithium niobate (LiNbO3)

See also

- Born-Infeld action

- Filament propagation

- Category:Nonlinear optical materials

- Parametric process (optics)

Notes

- ^ http://www.nature.com/nature/journal/v396/n6712/abs/396653a0.html

- ^ http://prl.aps.org/abstract/PRL/v76/i17/p3116_1

- ^ http://pop.aip.org/phpaen/v12/i9/p093106_s1

- ^ http://www.nature.com/nphys/journal/v3/n6/full/nphys595.html

- ^ Paschotta, Rüdiger, "Parametric Nonlinearities", Encyclopedia of Laser Physics and Technology, http://www.rp-photonics.com/parametric_nonlinearities.html

- ^ See Section Parametric versus Nonparametric Processes, Nonlinear Optics by Robert W. Boyd (3rd ed.), pp. 13-15.

- ^ Robert W. Boyd, Nonlinear optics, Third edition, Chapter 2.3.

- ^ Scientific American, December 1985, "Phase Conjugation," by Vladimir Shkunov and Boris Zel'dovich.

- ^ Scientific American, January 1986, "Applications of Optical Phase Conjugation," by David M. Pepper.

- ^ Scientific American, October 1990, "The Photorefractive Effect," by David M. Pepper, Jack Feinberg, and Nicolai V. Kukhtarev.

References

Boyd, Robert (2008). Nonlinear Optics (3rd ed.). Academic Press. ISBN 978-0123694706. http://www.amazon.com/Nonlinear-Optics-Third-Robert-Boyd/dp/0123694701/ref=sr_1_1?ie=UTF8&qid=1313111421&sr=8-1.

Shen, Yuen-Ron (2002). The Principles of Nonlinear Optics. Wiley-Interscience. ISBN 978-0471430803. http://www.amazon.com/Principles-Nonlinear-Optics-Classics-Library/dp/0471430803/ref=sr_1_1?ie=UTF8&qid=1313111556&sr=8-1.

Agrawal, Govind (2006). Nonlinear Fiber Optics (4th ed.). Academic Press. ISBN 978-0123695161. http://www.amazon.com/Nonlinear-Fiber-Optics-Fourth-Photonics/dp/0123695163/ref=sr_1_1?s=books&ie=UTF8&qid=1313111745&sr=1-1.

External links

- Encyclopedia of laser physics and technology, with content on nonlinear optics, by Rüdiger Paschotta

- An Intuitive Explanation of Phase Conjugation

- AdvR - NLO Frequency Conversion in KTP Waveguides

- SNLO - Nonlinear Optics Design Software

![\begin{align}

P^{NL}= \chi^{(2)} E^2(t)

&= \chi^{(2)} [

|E_1|^2e^{-i2\omega_1t}%2B|E_2|^2e^{-i2\omega_2t}\\

&\qquad%2B2E_1E_2e^{-i(\omega_1%2B\omega_2)t}\\

&\qquad%2B2E_1E_2^*e^{-i(\omega_1-\omega_2)t}\\

&\qquad%2B2\left(|E_1|%2B|E_2|\right)e^{0}],

\end{align}](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/bd7ab8017ee6dad4e45430a825e896da.png)

)

)